May 20, 2011

Giuseppe Filianoti

Classical Beat | Anne Midgette

Giuseppe Filianoti will perform in Jules Massenet’s, “Werther,” with the Washington Concert Opera at the Lisner Auditorium on May 22.

In 2007, the Italian tenor Giuseppe Filianoti gave a triumphant New York performance in Francesco Cilea’s opera “L’Arlesiana” at Carnegie Hall. Filianoti, 33, had won fans in his Metropolitan Opera debut; this performance cemented the love. “Remember his name,” said the Associated Press. “He’s going to be a major tenor.”

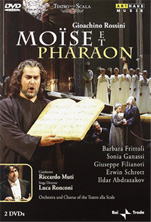

In 2008, Filianoti was in the headlines again — because La Scala had uninvited him from its opening night at the very last minute. In Milan, Filianoti was supposed to sing the title role of Verdi’s “Don Carlo,” a significantly heavier part for his light, lyric voice. Was the problem a mistake he made during the dress rehearsal; general backstage intrigue; or the fact that he was over-singing, taking on roles that were too big for him?

Officially, all is well again. Filianoti is going back to La Scala in December to open the season in the lighter role of Don Ottavio in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni.” He recently had some good nights — and some shaky ones — at the Met in “Rigoletto.” And Sunday at George Washington University’s Lisner Auditorium, he’s singing the title role in Massenet’s “Werther” with the Washington Concert Opera. But there’s no question he’s in the process of earning back listeners’ interest.

His trajectory mirrors that of all too many tenors. Roberto Alagna, Salvatore Licitra, Marcelo Alvarez, Rolando Villazon: All were hailed as future superstars, none quite met their promise, all are working on comebacks of various kinds.

Villazon’s fall was the most spectacular. His ardent performances captured the hearts of a broad public for a few years, but he over-sang so thoroughly that it led to operations on his throat, complete vocal rest and a couple of abortive comeback attempts. He’s now in the middle of a run of “Werthers” at Covent Garden that some are hailing as a true return to form.

Why are so many tenors falling by the wayside? For one thing, everyone is far too quick to overhype young singers, and offer them inappropriate roles. For another, inadequate vocal training leaves some singers uncertain about what they need to do to sustain the pressures of singing day in, day out in big repertory. But the greatest problem of all may be that the business of opera, as it is currently constellated, leaves singers unclear about their goals, aiming not for artistic excellence, but simply for survival.

“In modern life,” says Licitra, 43, speaking from Milan, “it looks impossible to get a career like Placido Domingo, like Luciano Pavarotti, like the glorious tenors of the past. Because this field, it’s [a] mess. The people working in it, they are ill-prepared. I mean from the theater, even the managers, they are concentrated just on organizing some product ready to sell and sell easily by TV.

“When something happens wrong and your voice is not able to perform any more, it’s scary because nobody cares,” he goes on. “Almost everybody is thinking it’s normal to have a short career like that.”

Licitra’s career-making moment came in 2002, when he jumped in as a last-minute replacement for Pavarotti in a “Tosca” that was to have been Pavarotti’s last Met performance. Media and audiences alike were quick to hail the passing of the torch. Licitra had the mien of a handsome teddy bear and a big, ringing voice, and he had been singing major roles at La Scala. He was widely feted as the next tenor sensation — so much so that Sony Classical followed his debut CD with an ill-conceived Three Tenor spinoff called “Duetto,” with him and Alvarez in souped-up pop arrangements.