Mar 15, 2013

The Exclusive Opera Lively Interview with Giuseppe Filianoti

Artist – Giuseppe Filianoti

Fach – Lyric tenor

Born in – Reggio Calabria, Italy

Currently in – Rigoletto, Lyric Opera of Chicago – Feb 25, March 1, 4, 7, 10, 14, 20, 23, 27, 30, 2013 – click [here] for tickets

Next in – La Clemenza di Tito, Teatro Lirico Giuseppe Verdi, Trieste, Italy – April 13, 17, 20, 24, 27 – click [here] for more information

Artistic Biography

While the majority of his performances have centered on the bel canto and later 19th-century lyric Italian and French works, he has also successfully essayed roles by Cherubini and Mozart through those of such 20th century masters as Strauss, Debussy, and Stravinsky.Among the tenor’s engagements in the 2012-13 season are: a guest appearance by the Teatro alla Scala at Moscow’s Bolshoi Theater in Don Giovanni (September); the Verdi Requiem in Strasbourg (September); both La clemenza di Tito (November/December, including a “Live in HD” performance) and La rondine (January) at the Metropolitan Opera; Rigoletto with Lyric Opera of Chicago (March); La clemenza di Tito for his company debut at Trieste’s Teatro Lirico Giuseppe Verdi (April); Les contes d’Hoffmann at the Bayerische Staatsoper (May/June); and further Rigolettos at Aix-en-Provence (June/July).

Born in Reggio Calabria in 1974, the Italian tenor first obtained a degree in Literature, a background he considers to be essential to his operatic foundation and discipline. In 1997, he graduated from the “F. Cilea” Conservatory, studying under Anna Vandi. Mr. Filianoti won a highly-coveted two-year scholarship to Milan’s Accademia del Teatro alla Scala. During this period of intensive fine-tuning of his voice, he met Alfred Kraus, who became his mentor and the decisive influence in helping the young singer develop his artistic style, technique and virtuosity.

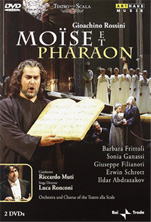

Mr. Filianoti made his debut in 1998 at Bergamo as Dom Sébastien. In 1999, after singing Argirio in Tancredi at the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro, he was engaged by Riccardo Muti to sing in Paisiello’s Nina, o sia pazza per amore. In 2003, again under Mo. Muti, he opened the season of La Scala with Rossini’s Moïse et Pharaon. He made his Covent Garden debut in 2000 as Alfredo in La traviata, returning there in the title role of Donizetti’s Dom Sébastien in 2005 and more recently as Nemorino in L’elisir d’amore. He is a frequent guest at La Scala, where he has performed in Falstaff, Rigoletto, Lucrezia Borgia, Gianni Schicchi, Un giorno di regno, and Lucia di Lammermoor. At Rome’s Teatro dell’Opera he has sung Faust, Gianni Schicchi, Die Zauberflöte and Werther, and made his debut with the Accademia di Santa Cecilia in a concert version of Idomeneo.

In 2005 he made his widely celebrated American debut at the Metropolitan Opera as Edgardo in Lucia di Lammermoor. In subsequent seasons he returned to the Company as Edgardo, as well as in many of his other signature roles, including Nemorino, Il duca di Mantova, Ruggero (La rondine) and Hoffmann. In addition to the Met, in the U.S. he has also appeared to great acclaim at the San Francisco Opera as Edgardo and at New York’s Carnegie Hall as Federico in Cilea’s L’Arlesiana. Nemorino was the role of his debut at the Los Angeles Opera in 2009, as well as at Lyric Opera of Chicago in 2010, where he returned in 2011 for Edgardo. The vehicle for Mr. Filianoti’s debut with Washington Concert Opera was the title role in Werther, one of his favorite operas. His US recital debut took place on the Harriman Jewell Series in April 2012.

Additionally, Mr. Filianoti has performed in the major European opera houses: with both companies in Berlin (Faust / Deutsche Oper); the Verdi Requiem (at the Philharmonie) and Don Giovanni, for the Staatsoper, both under Daniel Barenboim; Vienna (Traviata, Elisir and Lucia); Barcelona (Traviata, Rigoletto, Elisir and Lucia); Florence (Traviata, Zauberflöte and Don Giovanni); Hamburg (Idomeneo, Hoffmann La bohème and Faust); Madrid (Traviata, Werther and Celos aun del aire matan); Paris (Rondine, Elisir, Hoffmann and Manon).

In 2004, Giuseppe Filianoti was awarded the Franco Abbiati Italian Critics´ Prize as Best Singer of the Year.

Discography

The tenor regularly expands his diverse discography and videography. Among the CDs are: on the Bongiovanni label, Giuseppe Sarti’s Giulio Sabino (Ottavio Dantone, cond.) and Lucrezia Borgia (Mariella Devia, Marianna Pizzolato, Marco Guidarini, Cond.); on ROF, Tancredi (from Pesaro, with Daniela Barcellona; Gianluigi Gelmetti conducting); on Opera Rara, Donizetti’s Dom Sébastien (with Vesselina Kasarova and Simon Keenlyside, Mark Elder, Cond.), for Naxos, Boito’s Mefistofele (with Dimitra Theodossiou and Ferruccio Furlanetto, led by Stefano Ranzani); on the BMG/Ricordi label, Paisiello’s Nina (Anna Caterina Antonacci, Juan Diego Flórez, Michele Pertusi, Riccardo Muti/La Scala.)

Among his performances preserved on DVD are: Cherubini’s Medea (Hardy Classics) with Ms. Antonacci and Sara Mingardo, Evelino Pidò, Cond. from Torino; Rossini´s Moïse et Pharaon (on the TDK & ARTHAUS MUSIK labels), with Barbara Frittoli, Ildar Abdrazakov & Erwin Schrott, Mo. Muti/La Scala); La traviata (on La Voce) with Mariella Devia and Renato Bruson; Mefistofele on the Dynamic label (same cast as the previously-listed CD); and a 2007 New Year’s Gala Concert from the Teatro La Fenice with Ms. Theodossiou and Roberto Frontali). This season, a live recording of Cilea’s L’arlesiana will be released by CPO, including previously unperformed music.

————

OL – Today, you are one of the world’s leading lyric tenors, but the first university degree you received was in literature. Was singing then not your first career choice?

GF – Yes, I earned a degree in literature, but it was simultaneous with my degree in singing at the Conservatory. I earned both at the same time, in 1997. My passion was singing music, I was born with it. But my other passion was and still is literature. Maybe my first dream was to write books or to be a journalist, or get involved in research in English literature, Italian literature, everything. But when I started my musical training in the Conservatory in my hometown, I discovered that I had a gift. My teacher entered me in some competitions, and every time I’d win the first prize. So that kind of life took first place in my interest. Today I read a lot of books; they are my best friends when I’m alone and not working as a singer.

OL – So, you graduated from the Universita degli Studi in Messina, and you went through voice studies at the Francesco Cilea Conservatory.

GF – Yes, the literature degree was in Messina, Sicily, but the Conservatorio Francesco Cilea is in my hometown of Reggio Calabria in the mainland, separated from the island of Sicily by the Strait of Messina. So I was attending the Conservatory in my hometown in Calabria, but took the boat daily, to go to Messina in Sicily, to study at the university.

OL – What previous experience in singing did you have before you entered the conservatory? Were you a member of the choir at your school or church?

GF – Yes, I have to be very grateful to the sisters. My first school was run by Catholic nuns. Every morning we had to pray to God, and there was a choir to go together with these religious rituals, and I was a member from the time I was very young, six years old. So, the sisters would ask me, “Giuseppe, sing less loudly” because my voice would predominate over the choir. So, they decided to put me as a soloist. For five years, every morning the choir would sing with me in this position of soloist. Singing was a natural gift and a pleasure for me, and the sisters immediately discovered it. I have to thank them for putting me through this experience. For them, the praying and the singing was just as important as studying the school subjects.

OL – Were your parents and siblings also interested in classical music?

GF – No, in my family I was the first one. And I’m still the only one. [laughs]

OL – When did you attend your first opera performance? Which opera was it? What impressed you the most about the experience?

GF – My first opera was in Messina. In my town of Reggio Calabria we had a beautiful, beautiful theater but it was never put to work. The closest real opera house was in Messina. I went there to attend live opera for the first time, and if I’m not mistaken, it was Il Barbiere di Siviglia with Rockwell Blake. The second one was La Traviata, with Salvatore Fisichella. At the time I already loved opera and knew very well about the stories, and knew the arias and duets of the most famous operas. So, when I saw live opera on stage for the first time, it was a nice experience, I was fascinated by that. I immediately wished that one day I would do the same, on the operatic stage.

OL – I interviewed Luca Pisaroni. He grew up in Busseto in Giuseppe Verdi’s home region.

GF – Oh, wow!

OL – Yes. He said that as a young boy who loved opera in Italy, he was considered by his classmates to be weird, because all the other boys were into soccer, and he was into opera [laughs]. Was it something that happened to you as well?

GF – [laughs] No. When I started to really learn how to sing opera, I was in high school, around the age of fifteen to seventeen. When my classmates discovered that I could sing opera, they actually appreciated it, and they always asked me to sing at school, before the lessons started. They would tell me, “Oh, you’re like Pavarotti, please sing for us!” But they did find it a bit strange, that style of singing, and some of them would ask, “what is that??” Because in our culture, the opera lirica is not as popular now as it was in the past. I am thirty-nine years old now, so when I was a teenager, we were in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, and it was a very different situation from the 1950’s and 1960’s when everybody was in love with opera. So, at the time, I was trying to imitate Pavarotti, but I did it because I listened to him on my own and loved it, not because of a family tradition or a shared interest with my classmates.

OL – You also won a two-year scholarship to the Accademia at La Scala. Can you tell us what your two years there were like? What sort of training do the young singers there receive?

GF – This was one of the best experiences of my life. I grew up in a small city in the South, so, being in Milan at La Scala which is the premier place for opera in Italy was really exciting. I went there and auditioned for Maestro Riccardo Muti, and he immediately said, “OK, stop the audition, I want this tenor!” And after that, he followed my career very closely, and I have to thank him, because he always wanted me around and I learned a lot from him. He taught me how to sing opera, how to respect a composer, how to do the phrasing. Over there at the Accademia, another very important person in my learning was Leyla Gencer [editor’s note – the famous Turk soprano who became the teacher of operatic interpretation and the artistic director of the Accademia for young opera singers at La Scala, once she retired from the stage]. She had this big quality of the old style of fraseggio, and was an expert in interpretation. I learned how important words are in opera, not just the sound. It is important to interpret the feelings and show the results through the words. One also needs to know how to not exaggerate in the interpretation – you can’t do too much, but you can’t do too little, you need to reach equilibrium. The Accademia taught us the best Italian traditions that unfortunately we are now losing, even in Italy. It was a very good experience, yes.

OL – While you were there, you met the great tenor Alfredo Kraus, and he became your mentor. Of all the things you learned from him about style, artistry, and technique, what do you consider some of the most important?

GF – Alfredo Kraus was unique in opera. He was the living tenor that was closest to my taste. He was always a clear singer. He had perfect control of his breath and of his singing technique. He was also a gentleman, as a man. I think having him as a mentor was the most important experience I ever had, not only in Milan, but later. He was always open to giving me his impressions and advice. Of course, along the years, there were many great singers, but if I have to chose an interpretation to look up to, I always choose Kraus’s version, for his elegance and nobility.

OL – Yes, and he had a lot of longevity in his career.

GF – Yes, he took a lot of care regarding his voice. That’s important. Every singer is different, and the repertory never works the same for each person. But Alfredo Kraus was able to feel his body. If he understood that he was going against his body, he would always stop, and say, “no, this doesn’t work for me or for my voice.” You should never push beyond what your voice can do. This is what all singers need to do; we need to listen to our bodies and respect them. We are like sportsmen. We work with our minds but also with our bodies. If you use up your body too much or the wrong way, you’ll lose your body and you won’t be able to sing any longer.

OL – You made your professional debut when you were 24 years old, singing the title role in Dom Sebastien at Bergamo. By your mid-20s, you had made debuts in leading roles at some of the world’s major international opera houses. So you rose to the top of your profession very quickly. For some people, early fame can spell trouble; they don’t handle it well. How did you keep your emotional balance?

GF – That’s true. I started singing at La Scala at a young age, but I was lucky in the fact that I didn’t get prematurely involved with a recording label. Sometimes these labels throw their artists too quickly into worldwide exposure, and people make mistakes. I made my small mistakes as well at the beginning of my career but then I learned with my mistakes and learned how to manage my career. Today, the problem resides in the fact that sometimes these recording labels decide to make a star out of someone, but there is nothing there to sustain it. Maybe these artificially made stars can sustain it for one or two years, but then, if you don’t have a very strong mind and good ability to know yourself, your career can destroy you.

But I was very lucky in my beginnings. I was able to sing with the best stars and the best directors, and learned a lot from them. I sang with Renato Bruson, Mariella Devia, Daniela Dessì, who were the best ones in my generation. I was able to develop some good experience out of the Italian theaters, and when I went on to other major houses in the world, yes, it was fast, but never under too much pressure.

In the past, this was how it went for everybody, including Pavarotti, Kraus… today it is different. Today instead of this gradual learning and exposure, there is this publicity machine that takes people in their first or second year and convinces them that they’re the best, and put them out there on TV and so forth. I was lucky to have been spared this business-oriented model when I was learning the ropes.

OL – You won several important awards, and the second prize at the 1999 Operalia. How was that experience for you?

GF – It was very important for me. Before that, I had won another one that was very instrumental for me as well, the Francisco Viñas Competition in Barcelona. I won the first prize in the Viñas, and immediately after I won the second prize at the 1999 Operalia in Puerto Rico, the Domingo competition. I shared second prize with Rolando Villazón. The first prize was won by the Bulgarian bass, Olin Anastassov. Joseph Calleja also won a prize at that Operalia; he was the youngest prize-winner. We were all there in the same competition; it is a nice memory to have.

OL – And did Domingo open doors for you? Did he help you in any way after the competition?

GF – Domingo is a wonderful person and singer. He always called me back. He called me to Los Angeles to sing L’Elisir d’Amore a few years ago. Just recently he called me for a concert at the Arena di Verona to celebrate the Operalia there. If I need something and I have to call him, he will get me what I need, for sure. I only have good things to say about him, and I have a big respect for him. I know that he is there, and if I need something he will help me.

OL – Word spreads very quickly around the opera world when a wonderful new talent has been discovered. Houses begin offering the new star all sorts of roles, and some of them may really not be appropriate for the individual’s voice at that point. Did you also have this experience? Perhaps some houses wanted to engage you for some of Verdi’s or Puccini’s heavier roles?

GF – Sometimes, yes, but not too often. I’ve had to deal with some strange demands, especially from some important directors, for example, for Pagliacci, or for Il Trovatore, or many times for Norma, but I knew they weren’t roles for me. They may think, “all right, we need a lyric voice and not a spinto for this role.” It may even be an interesting experience to have, but you cannot cancel the tradition that is behind these roles, and the audience is savvy enough to balk at these vocal compromises. It’s better not to risk this sort of thing, so, I have always turned down offers that I thought were not well suited for my voice. Why should someone take on those risks? So, yes, I had this kind of experience, but was wise enough to say, “better not!” [laughs]

OL – Most of the roles you’ve sung are clearly in the lyric tenor repertoire. But you’ve also expressed elsewhere the desire to sing Peter Grimes, and you are under contract to sing Pelléas in the near future. Grimes is often sung by a heldentenor, though Britten actually wrote the role for a lyric tenor. But Pelléas really is a baritone role. A tenor can sing it, but aren’t there technical challenges involved in that?

GF – True, I have accepted this Pelléas et Mélisande, and yes, I’m a lyric tenor, so this appears to be in contradiction with what I was just saying, but there is a particularity. If you listen to my lower notes, I’m OK with that; I can sing in the lower register. My voice is not that of a leggiero that would have a lot of difficulty with the lower notes. I can easily lower my voice without forcing it. I consider this opera as one of the best in the 20th century, I love this opera and I love Debussy. It is so difficult, but musically it is something special. So, I said “yes, I want to have this experience,” like I did with The Rake’s Progress and with Capriccio, because I think we should give ourselves the pleasure of singing some beautiful music that we love. These are less popular works than, for instance, a Rigoletto or a Lucia, but sometimes you need to enjoy your work by doing something that is on a higher personal level for you.

OL – Right, if you like literature so much, you must enjoy the libretto for Pelléas et Mélisande, which possesses high literary quality.

GF – Yes, exactly! And not only that, but the music has such a great atmosphere! It’s like a symphony! It’s nice to go a little bit outside of lyric opera and explore another style. I like it when a role comes around that is not among the biggest workhorses. such as La Clemenza di Tito – it’s Mozart but not among his most famous four operas – and I love Mozart. And I know that Mozart is not really for my voice, because my voice is better suited for Werther, Manon, and Hoffmann; that’s where I feel at home. But I am a musician, you understand? So I like to do music that I love, sometimes, as long as it doesn’t destroy my voice.

OL – Do you play any instruments?

GF – I play the piano.

OL – You’ve also sung Stravinsky’s Tom Rakewell and you’ve expressed the wish to sing the title role in his Oedipus Rex. But you once described a lot of modern music as possibly overrated. What is it about Stravinsky’s music that appeals to you? Or perhaps should we no longer consider his works to be “modern” music?

GF – Yes, if someone asks me to sing Oedipus Rex, I’ll say yes. Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress is a masterpiece. I enjoyed playing the role of Tom, and I enjoyed learning it. It is a very difficult role to learn and remember, and it is hard to keep up with what is going on in the orchestra. The story is wonderful. So, I definitely don’t consider Stravinsky to be overrated. There is quality there, unlike in some other modern pieces.

OL – What about operas from the late 20th century or the 21st century? Are there any contemporary roles that you would like to sing?

GF – No, I think this is not something for me. There is too much dissonance in this music. I think we are going too far with that. I believe that the singing voice still needs at least a little bit of melody. I don’t feel comfortable when it is extremely dissonant. The modern works I’ve mentioned before are still sufficiently melodic, but the contemporary ones are not for me.

OL – You’ve sung Ruggero in La Rondine. What alternative ending do you prefer? The one where he confronts and abandons Magda who then kills herself, or the one where she abandons him and he begs her to stay?

GF – I think the ending where she kills herself doesn’t work. I’ve listened to it but I’ve never seen it live. I prefer the version that I just did at the Met, where she says, “this is not for us, bye, bye.” I think it is the easiest and simplest way to end that opera. I don’t think we need to make of Magda something very tragic. This is an especially light opera, in terms of Puccini’s output. I don’t think the big drama suits it well, like it does in the similar story that is in Verdi’s Traviata. La Rondine is what it is, a lighter story. Puccini tried to change the ending to give more power to the drama, but then this kind of tragedy is not compatible with the rest of the opera.

OL – Yes, La Rondine was commissioned as an operetta, originally.

GF – Yes, but then, Puccini was not able to do it as an operetta [laughs]. It wasn’t in him! So, he said, “let’s put some drama into it, now!” But the opera wasn’t born this way, and you can listen to the lightness in the score, so if you change the ending, you destroy the structure of the work, the way it was born.

OL – Yes, interesting. But let’s go back a little to Maestro Riccardo Muti who had, as you told us, a significant role in your early career. Opera Lively is scheduled to interview Maestro Muti in April. Can you give us a taste of what the great Maestro is like?

GF – Yes, Maestro Muti, I love him. He discovered me at La Scala, I worked a lot with him. He is very demanding. He wants professionalism from his singers and musicians. He studies a lot, and requires everything to be very clear and precisely worked. Every time I do something with him, I discover new aspects written in the music that I hadn’t noticed before, that nobody else was able to dig out. He masters the old tradition of Italian opera. I feel very lucky to be able to work with him. I must say, I believe him to be the best conductor, nowadays.

OL – Very nice. And is he very supportive of his singers?

GF – Yes, you know, he is very supportive of the opera! For him, what is very important is the music, and the opera. So if you demonstrate to him that you feel the same way, he will like you and support you to the end.

OL – I look forward to meeting him in person, for the interview that will happen in Chicago.

GF – Yes, you’ll see, he is very nice!

OL – Your background in literature must be instrumental to inform your stage work, right?

GF – Every time I prepare for a role and the libretto was taken from a work of literature, I make a point of reading and studying the source. The librettist needs to cut a lot of things from the source when writing the libretto in order to fit the story into the available time, given the added time for the music. So, if you want to have a wider and deeper understanding of the character, you need to go back and read the book. That’s very important, because then you discover little details that you can incorporate into your interpretation of the role, by yourself on the stage. For example, it was very important for me to explore the source for Werther. Sometimes you have to also explore history, to better understand historical characters like Titus in Mozart’s opera La Clemenza di Tito, and not only read the libretto by Caterino Mazzolà, but also go back to Metastasio’s piece, and study sources that give you some vision of the actual Titus. I always try to impart some meaning into my acting on stage, to do my work from the standpoint of an idea.

OL – Are there any books or plays that you think would be good source material for a new opera libretto that nobody has thought about, yet?

GF – It’s difficult to answer this. Books are something very individual. Everybody has his or her own relationship with a book. We like books because in them we find something to develop in our mind and feelings. I believe that books have literary value when they help in the understanding of human behavior and human feelings. So basically any book that fulfills this role can be turned into a good opera, because we go to the opera in search of the same thing – you want to get yourself immersed into the position of those characters, and to get involved with the dilemmas that they are going through. So, in our real lives today, people rarely stop to think about emotions, but if they go and watch La Traviata or La Bohème and they cry, it’s because these works put them back in touch with the deep human emotions that they may be skipping in today’s hectic world. Literary works achieve the status of classics exactly because they are able to evoke these emotions. So, there are many books that can qualify for a good opera – but then, if the music is not up to standards, even the best libretti won’t sustain an opera. You can have fantastic music with a bad libretto and still have a decent opera or even a masterpiece, but the opposite is not possible. So, if one selects a great book on which to base a libretto, it is still no guarantee that you’ll have a good opera, because you need to add exquisite music to it, so it’s hard to say what books would be successfully turned into great operas.

OL – You found a lost song from Cilea’s L’ Arlesiana, and made sure that it was incorporated into the score. This is unusual for a singer. Do you worry about critical editions, and what score is being used in your performances?

GF – This is a nice story; I found this song because I was born in the same city where Cilea was born. So I went to the Cilea museum there and found many manuscripts, and was reading through them, and found something that sounded very familiar to me, and I kept thinking, “where did I see this before?” Then I went to the first autograph copy of L’Arlesiana and it was there, but wasn’t in the subsequent editions that were being produced. It was the second aria for Federico, and it is very beautiful, so I asked the Maestro to put it in, and he did. But I don’t usually do that. For Cilea, it is a must for me, given our common origin. I want to do the best for his music. For other composers like Verdi, Wagner, Donizetti, Rossini, there are so many scholars that have looked into it; I don’t think it is up to the singer to do this kind of research. But in verismo, not everything has been discovered, so I was glad that I was able to do my small part to contribute to having a more complete and accurate version of L’Arlesiana.

OL – Back to our preparation for an opera role, you said you do extensive research on the literary source, when available. Regarding the musical side, how do you study the role?

GF – First, I listen to all the past recordings of the role, if possible. Then I play the piano score by myself, note by note. Next, I go to the voice coach and sing the role with piano accompaniment, to commit everything to memory.

OL – I’m always amazed at how you singers can memorize three hours of text and not miss a single word.

GF – It’s actually not so difficult, because there is the melody to guide you. The melody gets so closely associated with the words in a singer’s mind that when you are singing the melodies the words seem to just pop up and be the right ones. If you use the wrong word it suddenly doesn’t feel right. Think of a well known pop song – if you had to memorize the lyrics and recite them like a poem without the music, you would likely make more mistakes than if you had to just sing the song, then the words would come to you. Well, I can say this, but maybe it is not true for everybody. For me, it’s this way.

OL – Yes, it must have to do with how a musician’s brain is wired; what seems very easy to a singer may not be so easy for a regular person. Beyond the singing, there’s also the acting. Many reviewers have praised your acting skills as well as your singing. You also have some theatrical background, don’t you?

GF – I’ve been lucky to have worked with some of the very, very best stage directors. But I think to be frank that I do have a natural gift for acting. So, I take my acting very seriously. Every time a stage director wants me to do something, I need to be convinced. I want the audience to understand my character, and that is very important to me. So I have my own strong ideas about the acting, and I need to work with the director on them until we’re both comfortable with what I’ll be doing on stage. Because many times, what you do in your acting is closely related to the music, so the two need to really fit together, and the directors need to have an understanding of this. Voice, and acting – one doesn’t need to destroy the other one. They have to be integrated into one whole.

OL – You’ve sung the Lensky aria from Eugene Onegin in concerts, although I believe you haven’t done the complete role on stage. The Slavic languages can sometimes be difficult to learn for people who are native speakers of the Western European languages. Did you have to work with a coach or teacher on the Russian pronunciation?

GF – It’s not difficult to sing in another language, for me. I sing a lot in French but I don’t speak French. I think that the pronunciation for a singer comes with the territory, because if you are an operatic singer, you have a special skill for the musicality of sound; in the music, but also in speech. So, the sounds of speech even if they come in an unfamiliar language, are easy to discern and reproduce, for a trained singer.

OL – You frequently sing at La Scala, which has long been one of the world’s most important opera houses, and one with many traditions. One of those traditions is a very passionate, vocal audience that doesn’t hesitate to let those onstage know what it thinks. The loggionisti are legendary. Many famous singers have discovered what it’s like to displease a La Scala audience. But all of your experiences there have been positive, haven’t they?

GF – Yes, I had beautiful experiences there. But I don’t like the way they treat the singers. We need to respect the singers. There is a long tradition there at La Scala that the ticket-paying audience is entitled to expressing exuberantly their dislike, but one needs to understand that a singer who goes on the stage is always trying to do his or her best. The singer is not trying to live a lie and fool the audience, the singer is trying to do his or her job to the best of his or her ability, so, if the audience doesn’t like it, it is best not to applaud. Silence is very eloquent to a singer. There is no need to boo.

I was mostly lucky there at La Scala which was my home, the place where I was trained, so I have good memories from there and was given some love from the audience, as this local product – but I don’t like the way they treat some of the other singers. We are human beings, we give our lives to the art form and to be able to stand there on the stage and sing, while the audience gave only a couple of hours of their lives to that moment. Some of these behaviors can be very destructive to the mind of a singer; the audience should take that into consideration.

For the same reason, I don’t really read what the critics say. It’s easy to go and listen to someone, and write about it, and contest what the singer did. It is easy to judge. But it is not as easy to sing, and there is a lot that goes behind that in terms of effort and preparation, so, sure, singers can be criticized, but some measure of respect and some civility should still prevail.

This phenomenon is causing La Scala to self-destroy in a sense, because many big singers don’t want to go there to sing. The loggionisti at La Scala yell at the singers, tell them to go home, and that’s not so polite.

OL – When you made your debut at La Scala, were you at all concerned about the audience’s reaction?

GF – I was in a sense born there. Singing at La Scala for me is like singing at home. But still, every time I put my feet there, I’m scared, as is everybody! I’d be a liar if I said otherwise. Anybody who says “oh I don’t fear singing at La Scala at all, I’m just as relaxed there as in any other house” is a liar. Because they will find any little mistake, they will not let go of any little sound that you produce and is not what they expect. Never! [laughs] They did this to Callas, to everybody, so… [laughs]

OL – Opera is such an essential part of Italy’s culture. But with the current global economic problems, some opera houses in Europe and North America have been facing significant funding losses – whether from public or private sources. What is the current situation in Italy?

GF – It is the worst situation in Italy, among all the other countries. It’s a pity, I know, but it is true. Many opera houses are closing. They can no longer afford the important names in opera, and they’ve been asking the younger people to perform there; it’s not a good situation. In Italy we don’t have support from donors and philanthropists. It’s only from the state, and the state is giving close to nothing, now.

OL – Do you think the opera houses in Italy will be able to change their funding structure and survive?

GF – The problem is with the political situation. It seems like the current politicians in Italy are strongly against culture. I don’t know if the habit of sponsorship and donation can thrive in the Italian culture. We don’t have this type of behavior ingrained in our culture, so it is quite hard to start now. This is my opinion, I don’t know if it’s true or not, but I’m not optimistic about it.

OL – Will opera houses become more cautious and conservative in their productions?

GF – Yes. Some audiences may want to see something new and spectacular in the staging, but that costs more. You spend less money in paying singers and orchestras than you spend in the physical production, so, that part will also suffer. It may be a good thing, because some balance is needed. Maybe people will pay singers better if the productions are less ambitious. Big stagings, costumes, are very expensive, so, they’ll have to moderate that part, also.

OL – Avant-garde opera productions are very popular in the German-speaking countries. But what about Italy? Do houses and audiences there prefer more traditional stagings?

GF – In general, yes, but it depends. If you propose to the Italian public a very extreme production like we see in certain German houses, they will kill you, that’s true. If you do something modern but respectful to the text and the music and the opera, the Italian public will like it, it doesn’t necessarily need to be a traditionalist production to be successful in Italy. But when a stage director puts blood where there is none so to speak, and profoundly changes the opera, the Italian public will not accept it.

OL – Rigoletto in Chicago – how is it coming about?

GF – It’s a production from 2005 and it is a very, very traditional staging. It’s like going back to the past. Sometimes, it’s OK. It’s a pleasure. [laughs]

OL – Yes, we do tend to have more traditionalistic productions in the United States as compared to Europe. What do you prefer, the American or the European style?

GF – I wouldn’t properly talk about an American or European style. I’d rather say that I prefer what I call an intelligent staging. It can be modern, it can be traditionalistic, but if I work with someone like Graham Vick or Robert Carsen who do very intelligent work, I will accept just about anything, be it modern or not. They work very strongly in getting the best of the characterization for every singer. They do not try to say “this is not Rigoletto, now this is my opera, so I will change it.” No, for Vick or Carsen, first comes Verdi, then it’s the music, then it’s the libretto, and last is the staging. We put all these elements together, but they don’t try to impose anything that goes against the will of the composer.

OL – Have you ever refused to participate in a production when you profoundly disagree with the director?

GF – No, because I always try to find a solution. There is always a solution, if you talk to them and explain why it is not possible to do certain things. I have never been forced to do something very strange that I didn’t agree with, in my career.

OL – Mozart, Donizetti, Verdi, Puccini, and the French (Massenet, Gounod, Offenbach) – please tell us about your thoughts in terms of singing the music of these different composers.

GF – People say that Mozart is honey for the voice. Sincerely, this is quite a silly thing to say. It all depends on the way a singer is built. A big person with big vocal folds will be able to sing Wagner but then that same singer won’t be able to sing Mozart. Nature gives to each of us a different instrument, so you can’t say that Mozart is good for everybody. We lyric tenors are a bit lucky in this territory, because we often can do a little bit more or a little bit less and have a slightly wider range in our repertory, because we are not too leggiero, and not too dramatic. So, Gounod and Massenet are best for me, but I can still explore a little bit of Puccini, but not too much. Similarly, I can explore a little bit of Verdi, but not too much. I can however go back safely to Donizetti and Mozart, as I did.

But you can’t sing Mozart the same way you sing Puccini. If you are a lyric, you understand that singing Mozart teaches you a way to be more classical. It’s like a painting. If you see a classical painting, there is a particular beauty in it, and when you see a modern one, you can see another kind of realistic beauty. When you sing Mozart you have to sustain a beautiful tone, and stay there. When you sing Puccini, you need to go out and let go and give more passion. All these composers have different ways to work the musical line, a different style, and you need not only to have the appropriate voice for them in terms of weight, but also you need to understand the style and what kind of phrasing is expected of you.

Puccini has a warm color, but if you try to put too much color in Mozart’s music you’ll end up singing too loudly; you need to find a clearer voice for Mozart. Callas understood this very well. If you listen to her in a heavier role, then you go and listen to her Sonnambula, her color there is very different. She was able to adapt her voice to the style of the composer. But this notion that Mozart is honey is dangerous. Most people understand that singing a role that is heavier than what your voice can offer is damaging, but the reverse is also true. A heavier singer can also damage his voice by singing light Mozart. I’ve never sang Così fan tutte because I think it is too light for me.

OL – I particularly like your DVD of Medea with Ms. Antonacci, whom we’ve interviewed as well, a lovely and intelligent lady. Any memories of that production to share with us?

GF – Yes, she is something, Anna Caterina. That production had another great stage director, Hugo de Ana; I did some beautiful things with him. He did that staging with very low budget. All the costumes were second hand and recycled. There was only one set for the entire opera; the theater couldn’t afford any set changes. But he got the best of what could be done with that limited budget, by focusing on the feelings of the different characters. I remember him saying: “We need to put together this opera with the kind of atmosphere that we saw in the film Zorba, the Greek.” He wanted to recover that age full of superstition in the original story, in a sort of verismo acting coupled with the more ancient music. It was very nice; he was able to pull off this big contrast, but without disrespecting the music. That production was very beautiful.

OL – Yes, it was. Can you tell us about some of your plans for the future? Any new roles you are currently working on?

GF – I’m scheduled for several Rigolettos, but in terms of new roles for me, I’m studying Simon Boccanegra and I Due Foscari. I’m sort of retiring Mozart for now and going deeper into Verdi. Donizetti gave me so much… so another role I’m preparing is Roberto Devereux.

GF – What do you think of the future of the operatic art form in this hectic world we live in?

OL – I don’t know, it’s so strange now, they are trying to do a new kind of opera that is closer to the way the cinema industry approaches the audiences, with all the business side and the marketing and the polished images. But I try to do my best to help the kind of opera that I value continue to survive. However, an isolated singer can’t do much. The only thing we can do is to sing as best we can. I hope that money comes back to the arts. You cannot do good opera and enjoy opera without money. But I hope that the future will be less of this business-oriented model, and more of good musical quality.

OL -To finish, if you don’t mind, some more questions about your life outside opera. Are you married, do you have children? If yes, how do they relate to having an opera-singing daddy?

GF – I am married and have a son who is eight years old and lives in Italy. His name is Riccardo and he attends school. For him, my being a singer is normal; I’m just his Daddy, I don’t think the thinks of it in any special way. He went to see me in a few rehearsals. But now with him in school and with the fact that I sing so often outside of Italy, there isn’t much opportunity for him to see my work; it’s not so easy. But he saw all the videos that I have recorded. He tries to imitate my Rigoletto every time [laughs].

OL – Nice! What do you like to do besides opera? What kind of person are you, in terms of personality (outgoing, more reserved, etc.)?

GF – I like to read books, and to explore the city where I am, and see the local museums. As a person, I’m very reserved. So, those who know me well often ask me how I transform myself so much on stage. It’s probably because I have some things inside myself that I need to tell, and don’t normally do it with my reserved self. The best actors are those who have a lot to tell, and try to show it on the stage. In real life I’m just this normal guy, so the possibility of being another person on stage appeals to me. In real life, I think I’m very boring [laughs hard]. No, I’m kidding. I can actually be very funny with my closest friends. Most of my friends think that I’m very funny. I always find a way to make them laugh. But then, I also like to have my own time and to read my books, I don’t really enjoy going out and going somewhere with a lot of people to drink and so forth, it’s not my way.

OL – Thank you so much, this was a lovely interview.

GF – Oh, thank you. I loved it too. I’m happy that you liked it. Ciao!